A view from the ICRS Fort Lauderdale. Cruise ships, smoke stacks, palm trees, cargo containers, jets, and blue skies… Welcome to Port Everglades.

Once again, an impressive number of topics relevant to reef aquarists on the third day of the International Coral Reef Symposium. To summarize:

In a lecture on the genetic diversity of Heliofungia actinoformis populations in Indonesia, I learned that the global trade in live corals is worth between 200-330 million US dollars annually (and no doubt increasing). This represents between 11-12 million corals exported each year. That’s a lot of coral.

____________________________________________________________________

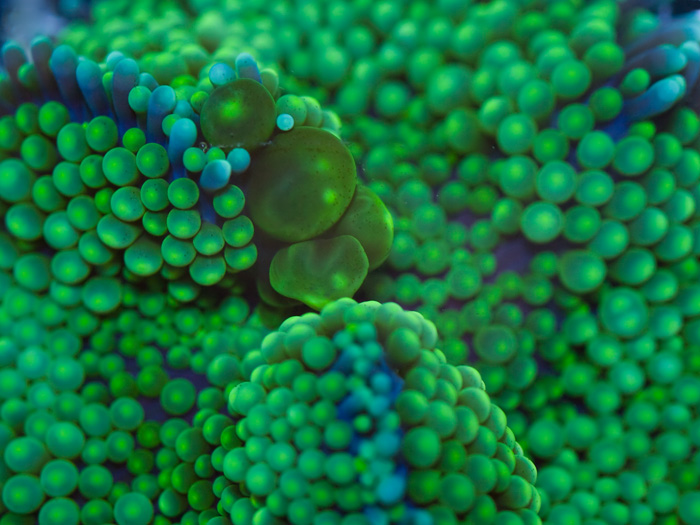

In an in-situ (lagoon based) coral aquaculture experiment in the Maldives, researchers concluded that the most efficient way to maximize the development of axial polyps (fast growing branch tip polyps) in Acropora muricata (a “staghorn” species) was to do the following:

- Use basal fragments (mid-branch, not branch tips, i.e. broken on both ends) laid down horizontally on the grow-out tray (perpendicular to the water surface).

- Induce injury (by scraping off sections of basal polyps) at several locations along the top of the fragment to encourage the development of axial polyps that will form new branches.

- The smallest fragment sizes in the experiment (3cm) maximized axial polyp formation. Productivity was increased by 75% by using three 3cm frags instead of one 9 cm frag.

It should be noted that the experiment took place in pristine water conditions, so survivability was nearly 100%. Algal overgrowth and disease was not an issue. I would expect that if this experiment took place in more nutrient laden water, that survivability would be reduced when inducing injury on such small fragments (3 cm). Nevertheless, I would have predicted the faster growth from branch tips rather than mid-section fragments, but in fact this sort of “pruning” clearly encourages the growth of multiple, fast-growing branches.

___________________________________________________________________

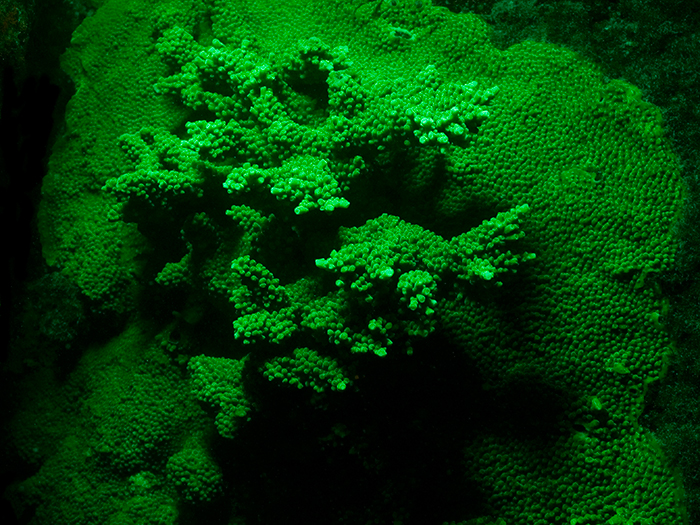

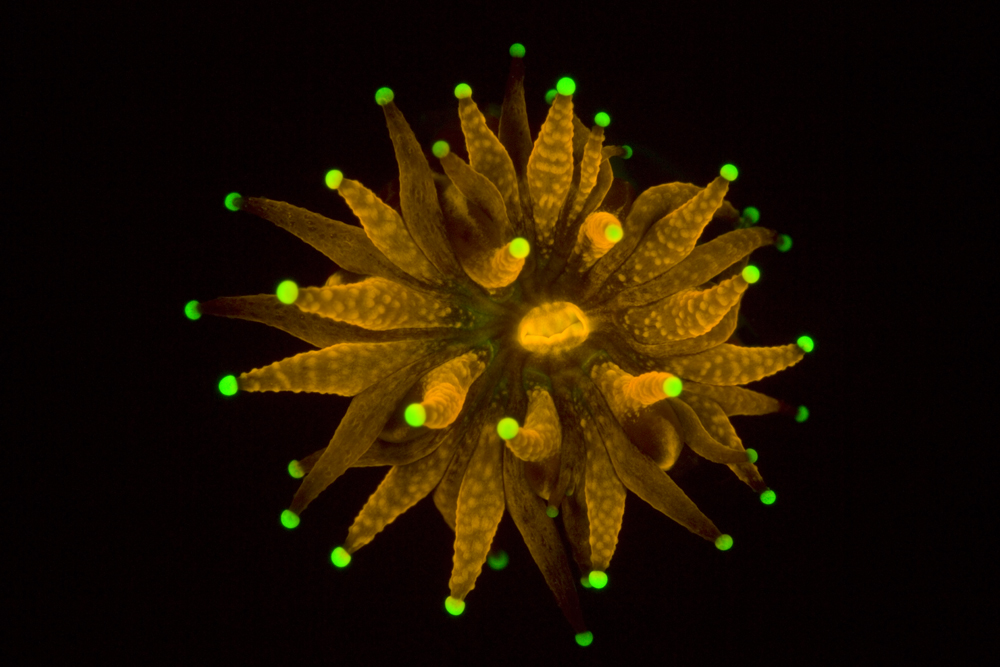

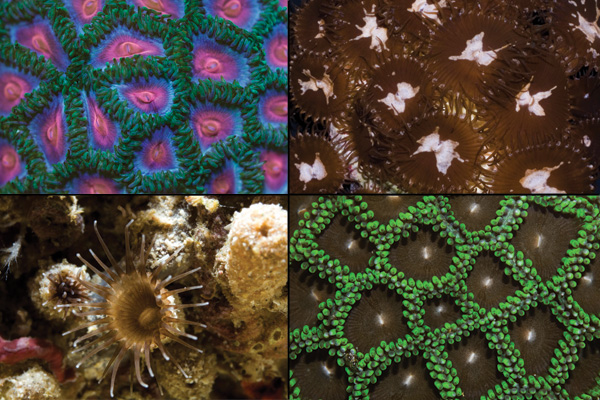

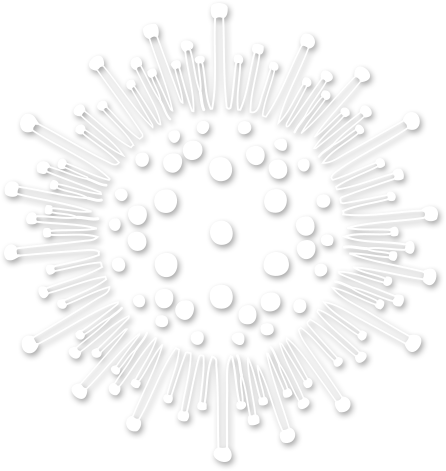

There was another interesting lecture entitled “Morphological Dependance of the Variation in the Light Amplification Capacity of the Coral Skeleton” that focused on the ability of a coral’s aragonite skeleton to amplify light by scattering it over a wider surface area, and ultimately providing surrounding polyps with more available light for photosynthesis.

The researchers tested different skeletal morphologies (i.e. massive, branching, plating, etc), and discovered that there was a clear correlation in light scattering depending on the corals’ growth form. For instance, the encrusting coral Porites branneri was able to absorb four times as much light over the same surface area as that of a smooth sea grass blade. Of all the corals tested Echinopora horrida (a branching coral) absorbed the most amount of light, where as Caulastrea furcata (phecelloid morphology i.e. polyps are separated with no connecting tissue) absorbed the least. It should be noted that Acropora branching corals scattered light so well that their lab equipment could not properly calculate the efficiency of this scattering. They estimate that Acropora is capable of absorbing more than 10 times the amount of light than what would otherwise hit a flat, non-aragonite surface. To summarize, they conclude the efficiency of light absorption more or less follows this morphological pattern:

(least) Solitary polyp < Phaceloid < Massive < Plating < Branching (Most)

___________________________________________________________________

A genetic analysis of the yellow tang (Zebrasoma flavescens) seemed to indicate the possibility that this species developed within the Hawaiian Archipelago (where it is common), and then more recently spreading south and west through the northern tropical/sub-tropical Pacific. Over this large geographic distance genetic variability was quite low, indicating wide larval dispersal carried by oceanic currents. Peculiarly, around the Big Island of Hawaii, up to four distinct genetic populations existed in rather close (but clearly separate) vicinities. It was posited that the yellow tang has not reached the Southern Indo-Pacific due to niche overlap and competition with the common scopas tang (Zebrasoma scopas). Where these two species occur at the same location, hybridization is common.

___________________________________________________________________

I got to spend some time with Brian Plankis and Eric Borneman to discuss their Project DIBS and Reef Stewardship Foundation. I will do my best to highlight these endeavors in a separate post. In the meantime check out their websites, and sign-up with Project DIBS (Desirable invertebrate Breeding Society).