Lower Keys Coral Bleaching Report (August 22, 2014)

Having been preoccupied with the Miami Coral Rescue Mission this summer, we finally made our first excursion to the Lower Keys this summer on Friday August 22. Sadly, we found that a distressingly high percentage of corals living on the reefs in Hawk Channel are severely bleached. Most of the staghorn corals that we saw were severely bleached or actively dying, though there were a few hardy exceptions. Nearly all of the brain corals were bone white. All over the reef we observed an unhealthy mix of cyanobacteria and algae proliferating on previously dead coral skeletons. Even the normally hardy gorgonians, corallimorphs, and zoanthids showed significant bleaching on all three patch reefs we checked. The water temperature was an uncomfortable 89 degrees on the bottom. Without strong winds or storms to cool off the water, we are concerned that many reefs in the Keys will lose significant coral cover in the next several months.

What is coral bleaching?

Bleaching occurs when a coral becomes stressed, and in response, expels its symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) from within its tissues. Normally, a healthy coral relies on this photosynthetic zooxanthellae to provide it with the extra energy it needs to grow and build reefs. But when deprived of this zooxanthellae, the coral begins to starve, and can become more susceptible to infection and eventual death. Water that is too hot, in conjunction with strong UV radiation from the Sun, is the likely cause of coral stress that lead to bleaching we observed in the Lower Keys. If the water cools down a few degrees in a timely fashion, it is possible for the coral to be recolonized by more stress-resistant strains of zooxanthellae, thus allowing these corals to be more resilient in the future.

Bleached staghorn coral, a federally protected threatened species.

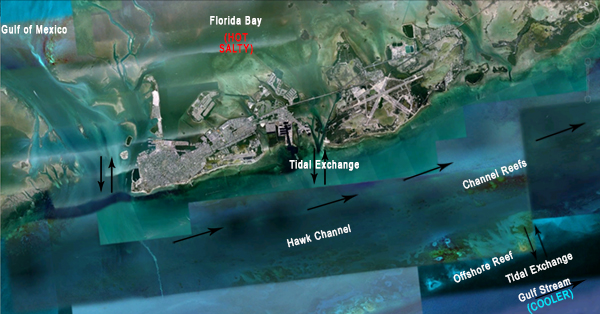

Unfortunately for the coral, the summer of 2014 has been particularly hot, sunny, and calm for the Keys. The Sun’s daily intensity drives water temperatures to exceed 90 degrees (32 C) in the shallow coastal bays, estuaries, and lagoons north of the Keys. At low tide, this hot water flows back offshore through the narrow passes between the Keys, and then into the deeper Hawk Channel. Hawk Channel runs parallel with the Florida Keys on the Atlantic side and carries the water northward along the coast. It is the confluence of these offshore and inshore waters in Hawk Channel that nurtures Florida’s most biologically diverse (and important) coral reefs.

With a lack of strong wind or tropical storms this year, the hot water from Florida Bay has not mixed well with the cooler Atlantic ocean water that comes in on the high tide from across the outer reefs. This has created two distinct layers of water (a thermocline) in Hawk Channel. Normally warm water floats on top of cool water, but in this case, the hot, green water from the Bay is actually more dense (because it is saltier), and thus it stays on the bottom where it is overheating the corals. We found the clear, blue surface water to be noticeably cooler at 87 degrees (30.5 C), but was also full of large, stinging moon jellyfish.

What the corals need as soon as possible are strong winds, dark skies, and rain to agitate, mix, and cool the water. We would never normally hope for a tropical storm in Florida this time of year, but it appears that that is exactly what the corals in the Florida Keys could benefit from. If the water temperature decreased a couple of degrees soon, most of the bleached corals will be able to recover by becoming recolonized by new zooxanthellae. However, if the hot calm weather continues unabated, then it is possible Florida could see widespread coral die-off this year.

A satellite view of the basic hydrology and water flow into Hawk Channel offshore Key West.