‘On Super Corals and Where to Find Them (A Closer Look at Miami’s Urban Coral Ecosystem)’ – Part 2

Read Part 2 (& Part 1) of our essay on super corals: ‘On Super Corals and Where to Find Them (A Closer Look at Miami’s Urban Coral Ecosystem)’ on Medium or click the link below:

On Super Corals and Where to Find Them

(A Closer Look at Miami’s Urban Coral Ecosystem)

Part 2

By Colin Foord, Co-Founder of Coral Morphologic, Miami, FL

Miami’s unique human-engineered waterways have inadvertently provided us with a crucible in which to observe corals evolving in real time. By encrusting the City’s infrastructure and cementing our detritus together, Miami’s urban corals demonstrate they are capable of colonizing our world in a post-sea level rise future.

Coral Morphologic first employed the adjective super to characterize an evolutionarily-advanced coral that had pioneered (as a larva) into a disturbed man-made environment, settled, and thrived to adulthood – as opposed to using the word to memeify a coral that has survived a bout of bleaching or disease. Because of the difficulties involved with determining the genet age of a coral in the wild, identifying so-called super corals is difficult on a natural reef. For instance, it is possible that a fist-sized coral could be a juvenile recruit just a few years post-metamorphosis, or it could be a lone-surviving clonal remnant of a coral that settled long before humans began belching industrial gases into the atmosphere.

Therefore, Coral Morphologic posits the surest way for scientists to identify these evolutionary trailblazers is to seek out the healthiest corals living on man-made infrastructure in a heavily-altered environment.

Fortunately for researchers, estimating the age of corals growing on submerged man-made infrastructure is simple, as most artificial habitats have a recorded date of deployment. Armed with historical information, a scientist is empowered to study these opportunistic corals with far more certainty of their birthdate than those encountered offshore on the natural reef tract. In Miami, we know the rocks colonized by corals along the MacArthur Causeway were placed there in the early 1990’s, whereas the riprap in front of PortMiami Pilot’s House was deployed in 2010, making it the perfect location to study a new generation of coral recruits.

The riprap at the easternmost tip of PortMiami was replaced in 2010, but it has since served as a coral transplant site related to the Port expansion, and natural recruits are now well established. This site now attracts a community of coral reef life (Coral Morphologic)

Coral Morphologic considers cross-breeding in the laboratory to be one of the most exciting developments in coral science today. But it isn’t until these young corals are subjected to a gauntlet of anthropogenic conditions that the weak genotypes are weeded out and the lab-bred super corals become apparent. While new technologies offer scientists the ability to mimic the conditions needed to intentionally produce hybrid super corals, the process takes a serious amount of time, money, and effort. As crucial as it is for scientists to be capable of reproducing corals in a captive aquarium system in 2018, it is important to note that these captive-born offspring will not be super corals any more than humans born of in vitro fertilization are super humans. And at the end of such an experiment, we are more likely to end up with corals better adapted to life in an aquarium instead of the degraded reef environments where transplants are needed most for restoration.

The sad truth is every anthropogenic factor that stresses or kills coral on the reef is also assisting in the evolution of their remaining wild gene pool. Because a metamorphosed coral cannot simply get up and move if the environmental conditions are not to its liking, the corals’ motto in the Anthropocene is the same as it’s been for the past 500 million years: adapt or die.

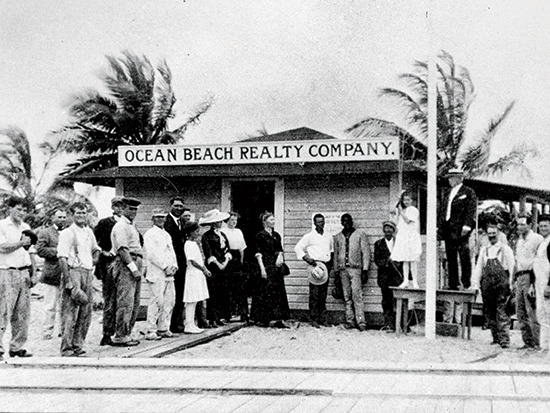

From its inception in 1915, Miami Beach has been regarded as a man-made real estate development to capitalize on (miami-history.com)

Why spend millions of dollars building a closed-system super coral lab that introduces multiple unnatural variables of captive coral aquaculture, when a real-world coral proving-ground already exists in one of the most heavily human-impacted environments on the planet?

It is precisely Miami’s legacy of anthropogenic disturbance that led Coral Morphologic to recognize that humanity could not have built a better laboratory to assist and accelerate the evolution of Floridian coral species.

The fluorescent protein-rich hybrid Acropora prolifera, the original ‘Super Coral’ (Coral Morphologic)

And so, after stumbling across the hybrid Acropora prolifera along PortMiami in 2009 (discussed in Part 1 of this essay), it dawned on me that here at scientists’ disposal was a real-world crucible in which to observe how corals will react to accumulating human impacts in the 21st century and beyond.

Miami is the Coral City; was, is, and always shall be. Built with limestone mined from the Everglades, Miami’s concrete skyline now stands like a community of corals colonizing the fossilized reef ridge the city was erected upon. The comparison of a coral reef to a city is not a new metaphor, but in Miami, the metaphor is literal.

As above, so below (Coral Morphologic)

At a time when corals were curios and reefs were hazards of navigation, Miami’s marine habitats came under assault from persistent dredging and unchecked urban development. However, an unintentional outcome of Miami’s early-20th century building boom was the emergence of a human-made coral haven here in the 21st. Because the shallow offshore reef tracts presented a danger to the very ships needed to transform Miami into a cosmopolitan port city, a deep channel, Government Cut, was dredged in 1905. Ever since, the Cut has served as a sluiceway to funnel reef-spawned coral larvae into North Biscayne Bay. The twice-daily tidal flow of clean offshore saltwater helped stabilize the chemistry and temperatures inside the Bay to a degree that these corals could not only settle on the infrastructure, but grow to adulthood.

Aerial photo of Government Cut circa 1916 showing a huge plume of outgoing coral-killing sediment (miami-history.com)

The first major reported coral die-off of the Anthropocene began in South Florida four decades ago, precipitated not by heat, but by a freak cold weather event in 1977 that brought Miami’s only recorded snow. First to go were the hurricane-protective thickets of elkhorn and staghorn Acropora corals, followed by the Diadema sea urchins which remove coral-competitive turf algae from the reef. By 1982, the wave of die-offs had accelerated and spread outward from Florida throughout the rest of the Caribbean Sea.

Incidentally, in all my time working as a coral biologist here in South Florida, the most acute coral mortality event I’ve witnessed was the prolonged cold snap of January 2010. News stories were full of descriptions of exotic iguanas falling from trees and millions of dead fish rotting in the mangroves. Much of Florida’s shallow coastal water (<4m deep) habitat was wiped clean of its tropical biodiversity. Nearly all of the nearshore corals, queen conchs, and Bahamian sea stars were wiped out by water temps that dipped to 10C (50F) for several days in some locations. It was one of the most heartbreaking and devastating climatic events I’ve ever experienced.

And yet the hybrid Acropora prolifera and nearly all the shallow-water urban corals of North Biscayne Bay survived. The continued vitality of these corals through the devastating cold snap reinforced to me that these were indeed some super-resilient corals, and it led to the subsequent TEDx talk in 2011 presenting them as such.

Thus it is with a serious dose of irony that my multiple attempts to draw local scientific interest towards these pioneering urban corals living in Miami’s waterways have been largely met with arms-crossed skepticism by pillars in the field.

Chris Langdon, professor and chair of the Department of Marine Biology at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, sees the Biscayne Bay corals as a “curiosity” that will be wiped out in the next severe cold snap. “They’re surviving at the limits of their natural range,” Langdon says. (Biscayne Times, January 2016)

As an inquisitive person, my first reaction to the fact that these “curiosities” “are surviving at the limits of their natural range” was that those are precisely the reasons why I think scientists should be studying them – not the reasons to not study them! To discount, overlook, or ignore the unique man-made conditions that have made North Biscayne Bay conducive to coral growth strikes me as a disquieting neglect of scientific inquiry, let alone basic human curiosity.

But perhaps our differences in perspective are generational. From the time I’ve been alive on Earth, the Caribbean has been perpetually plagued with an ever-increasing number of coral diseases – many of which still defy complete understanding of causative agents. The overall health and diversity of the region’s coral reefs has declined precipitously in recent decades, punctuated by spikes in mortality following bleaching years in 1998 and 2005, a cold snap in 2010 here in Florida, and back-to-back bleaching in 2014 and 2015. As a result, it is estimated that up to 97% of the critical reef-building Caribbean Acropora corals have died in the past four decades.

Since the Army Corps of Engineers’ Deep Dredge of PortMiami that began in late 2013 (see ‘Coral City’), a new wave of die-offs has hit South Florida’s reef-building brain corals. Colpophyllia natans, Meandrina meandrites, and Pseudodiploria strigosa have shown losses of 75-97% in recent years. The disease, which appears highly contagious, is exceptionally lethal – capable of wiping out decades-old coral colonies in days. Less conspicuous species that have received limited study, such as Eusmilia fastigiata, Scolymia cubensis, Dichocoenia stokesi, and Mussa angulosa appear to be disappearing from Florida’s reefs faster than scientists’ attempts to document their baseline populations. Researchers of this ‘white plague’ outbreak in Florida have declared “The high prevalence of disease, the number of susceptible species, and the high mortality of corals affected suggests this disease outbreak is arguably one of the most lethal ever recorded on a contemporary coral reef.”

Sediment in Government Cut resulting from port dredging, 2015 (Coral Morphologic)

Florida’s reefs have long been, and continue to be, some of the most beleaguered on the planet. As a result, Miami offers researchers a present-day ‘window into the future’ to better understand how corals may adapt to survive in less-than-ideal conditions globally.

Because so much coral has already been lost in Florida, it is perhaps too easy to overlook the grave situation in Miami when compared to the disaster unfolding on the Great Barrier Reef. After all, many people had already written off Miami’s coral reefs before the recent coral disease outbreak. But with stony coral cover now estimated at less than 7% on the Florida Reef Tract, it is easier than ever to portray our natural reefs as functionally dead and ignore the new generation of pioneering urban corals taking advantage of our City’s infrastructure.

As alarming as it may be to watch the formerly pristine, largest barrier reef system in the world experience back-to-back bleaching mortality events, the Great Barrier Reef continues to be many times larger, healthier and more diverse than any of our Florida (or Caribbean) reefs. To put it another way, Florida’s reefs are about four decades ahead of schedule when compared to the anthropogenic decline of more remote reefs on the planet. Florida’s 1977 may be akin to Australia’s 2014-2015; a dramatic tipping point that demands all-hands-on-deck to contain any further losses.

Yet here in Miami, at the historical epicenter of anthropogenically-impacted reefs, there exists a population of logic-defying corals not retreating away from the urban core, but rather pioneering directly towards it. This point is made abundantly clear by the fact that after four decades of severe coral decline on Florida’s natural reefs, the only place in the State that appears to be improving its coral health and biodiversity is within the manmade confines of North Biscayne Bay.

It is almost as if the corals are trying to tell us: “OK humans, now that the melting ice cap feedback loop is out of control, we’ll just wait here along the side of the highway until the seas rise and you all have to retreat. Then we’re going to colonize the abandoned concrete dwellings that you built from the bones of our ancestors. The clock is ticking, are you paying attention? This is gonna be our city soon, the Coral City. What are you gonna do about it?”

Cars driving through full-strength seawater on Miami Beach during a king-tide flooding event (Coral Morphologic)

So how is it that these urban corals have colonized one of the most iconic tourism destinations on Earth?

There are few ecosystems on the planet that have been so drastically altered by human terraforming as those of South Florida. When Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León arrived at the mouth of the Miami River 500 years ago, the prospect of corals living in North Biscayne Bay was simply not a biological possibility. Originally, the hydraulic pressure of the Everglades created a multitude of pristine, freshwater springs that bubbled up from the mouth of the Miami River all the way across the Bay to the barrier island now known as Miami Beach. It’s ironic that Spanish conquistador Ponce de León may have found (and overlooked) his “Fountain of Youth” that was actually Biscayne Bay itself. But it’s even more ironic it necessitated the Army Corps of Engineers to drain this vital freshwater source in order to build a city… and in the process inadvertently created the conditions needed by corals to survive in the middle of a metropolis.

The first bridge connecting Miami to Miami Beach was opened in 1913 and was for a time the longest wooden bridge in the world. It has since been replaced by the MacArthur Causeway (miami-history.com)

There are three major keys to understanding how the urban corals have been able to colonize Miami’s coastal marine ecosystem:

-

In the early 20th century, in order to control water flow through the Everglades, government engineers canalized its drainage and altered the flow such that only a small fraction of the freshwater continued to exit through the mouth of the Miami River into North Biscayne Bay (then a naturally brackish mangrove estuary). The resulting change in hydraulic pressure caused most of the freshwater springs to cease their flow.

-

To serve the fledgling city, a port was needed, so a deepwater channel (Government Cut) was carved in 1905 to guide ships through the shallow reef tracts into downtown Miami. Not only did this channel act as a conduit for ships, but also as a sluiceway for cleaner offshore water and coral larvae to be sucked into North Biscayne Bay on every incoming high tide. In 1925 a second inlet North of Miami Beach, Baker’s Haulover, was dredged. The resulting increase of the Bay’s flushing capacity helped to stabilize the conditions tropical corals need in order to survive at our subtropical latitude.

-

Much of Miami Beach’s current real estate was literally dredged from the bottom of North Biscayne Bay, and thus concrete seawalls and boulder riprap were the best means to protect this investment in terra firma from quickly eroding back into the water. The human-made aquatic hardscape finally offered corals a durable substrate to colonize in a Bay that previously had allowed minimal opportunity for larval settlement.

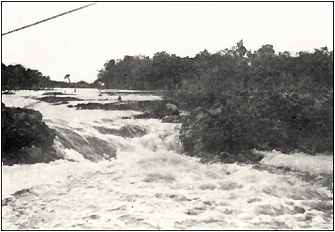

Miami River’s freshwater rapids circa 1909 before dredging allowed the introduction of saltwater (miami-history.com)

Government Cut circa 1927 looking West towards the Port and Downtown. Fisher Island is left, Miami Beach is right (miami-history.com)

By 1920 a public aquarium was built next to the terminus of the Causeway to Miami Beach. The seawall helped keep the newly dredged land in place. The 15,000 gallon aquarium cracked in its first year of operation. In true Miami-style, the aquarium was later busted as a speakeasy during prohibition. A century later, this seawall is now colonized by dozens of native species of corals and reef organisms (miami-history.com)

Consequently, a brackish domain previously inhospitable for corals a mere century ago was transformed through a series of major feats of human engineering into a relatively stable saltwater ecosystem. The Miami River, which once boasted a set of whitewater rapids, was dredged into a deep tidal canal that provided ships (and dolphins, manatees, etc.) a conduit out of the Bay and into the City.

Manatees have been longtime visitors of Biscayne Bay, in search of the seagrass meadows and freshwater springs that were once plentiful before humans made their mark on Miami (Coral Morphologic)

Along Star Island, an exclusive enclave dredged symmetrically into a pill-shape, there exists one of the most clear-cut examples of how stony corals are able to bind together rubble into an interconnected limestone reef structure. At this location one can find massive brain corals conjoining old pieces of concrete, bricks, wires and other refuse of the rich and famous. The contrasting imagery conjures up a potential vision of Miami’s post-sea level rise future, where the submerged rubble of our abandoned city will be overgrown with reef life.

Star Island offers an excellent opportunity to understand how corals build reefs. Here they can be seen overgrowing a century’s worth of discarded bricks, blocks, and wires, and cementing it all into a solid structure. Here is the most realistic look at Miami’s post-sea level rise future (Coral Morphologic)

Spansule-shaped Star Island is seen completed in 1920 and connected by bridge to the MacArthur Causeway. Note the smokestack belching pollution from the power plant along the Causeway on Terminal Island (miami-history.com)

MacArthur Causeway as seen from above the intersection with the Star Island Bridge. The deeper blue water of Government Cut along PortMiami to the south is juxtaposed with the shallow, greener water of North Biscayne Bay. Despite the considerable differences in environmental conditions, there are thriving corals on both sides of the Causeway, some of which are growing on trash and human debris (Coral Morphologic)

How is it possible that the healthiest populations of Colpophyllia brain corals in Miami-Dade County are now living within meters of non-stop car traffic? Does the constant glare of sodium vapor streetlights confuse the lunar reproductive cycles of the corals living there? Are these corals consuming microplastics? How are these corals thriving in water that is frequently flagged by the County as unsafe for humans to swim in due to elevated levels of fecal coliform and other pathogenic bacteria?

These are some of the questions that we are finally beginning to examine since partnering with Florida International University’s IMaGeS Lab in 2017. Starting with three different urban coral habitats, we have been sampling the microbiome of Colpophyllia natans and Siderastrea siderea corals to compare against microbiome samples of the same species collected offshore on natural reefs. Collecting tissue from ten adult C. natans colonies was a simple task along the highway, but it proved impossible on every single offshore reef sites we selected. All that we could find on the natural reef tract were recently dead C. natans coral heads and the occasional surviving polyp too small to safely sample.

More recently we teamed up with the ACCRETE Lab at NOAA/ University of Miami to study the transcriptome genetics of several species of urban corals, establish a research nursery, and deploy sensitive equipment to record temperature, pH, turbidity, alkalinity, redox potential, and dissolved oxygen levels. Our specific attention in this study is focused on Pseudodiploria strigosa (symmetrical brain coral) and Porites asteroides (mustard hill coral), both locally common in certain parts of North Biscayne Bay.

A 2018 satellite view of Miami to Miami Beach from above North Biscayne Bay centered on PortMiami (Dodge Island), the artificial islands of the Venetian Causeway and MacArthur Causeway with Palm, Hibiscus, and Star Islands connected by bridge. Fisher Island with its golf course is on the south side of Government Cut. Miami’s sewage treatment plant on Virginia Key can be seen south of Fisher Island (Google Earth)

It bears repeating that what makes a coral successful isn’t simply determined by the animal’s genetics. Corals are not singular animals, but holobionts – assemblages of different organisms that collectively make up what we call a ‘coral’ – a community unto itself. And thus a coral’s evolutionary fitness is influenced by both its genes and its microbial symbionts. The most well-studied coral symbionts are the photosynthetic zooxanthellae; strains of which, like Clade D Symbiodinium, offer differing tradeoffs in a global warming scenario. But in recent years, researchers have discovered a myriad of new microorganisms and viruses living symbiotically on corals’ mucosal surface tissues and within their skeletons that appear to act like a probiotic immune system.

During the same time period the Colpophyllia brain corals have been dying offshore of Miami due to the ‘white plague’ outbreak, the colonies living along the MacArthur Causeway have managed to thrive. It is our hypothesis that the microbiomes of these corals, living in a veritable stew of human wastes, are uniquely adapted to conditions one would expect to be prohibitively toxic. Is the ability of the urban corals to live successfully along a highway due to the inadvertent evolutionary ‘assistance’ our anthropogenic byproducts have on them?

A community of resilient corals has opportunistically colonized the limestone boulder riprap of the Miami Beach Marina. They are still living amidst a tremendous influx of pollution from boats fuel and coastal runoff, but benefit from the proximity to Government Cut (Coral Morphologic)A community of resilient corals has opportunistically colonized the limestone boulder riprap of the Miami Beach Marina. They are still living amidst a tremendous influx of pollution from boats fuel and coastal runoff, but benefit from the proximity to Government Cut (Coral Morphologic)

After a decade of studying the subtidal urban shorelines of Miami and discovering corals in places I never imagined possible, it doesn’t seem so far fetched that these corals are patiently waiting for the seas to continue their rise in order to recolonize the bones of their ancestors. The fact that the highest natural elevations in South Florida were built by corals demonstrates the extent of sea level rise in the past… and where we may be pushing them again in the future. The Everglades has not always been a monolithic freshwater river of grass. It has ranged from a dry prairie savannah 400’ above sea level at glacial maximum to a completely submerged marine ecosystem when the polar ice caps were melted.

Miami’s urban corals suggest that corals may very well outlast humanity here in South Florida, and they just may outlast us globally. After all, corals have been building underwater cities for ~500,000,000 years, while humans have only been doing so on land for about 5,000 years, roughly the average age of a coral reef. Perhaps us humans could serve to learn a thing or two from corals about life on Earth.

The primary insight gained from observing these urban corals is that at least some corals are more adaptive and resilient than many believe possible. When run through the evolutionary gauntlet that is Miami coastal living, a significant number of coral larvae appear capable of settling and thriving to adulthood. In short, these corals are worth studying.

By encouraging scientific investigation of Miami’s resilient urban corals, we hope it will help illuminate how these ancient holobionts are capable of evolving in the Anthropocene. Ultimately, we believe the story of the urban corals provides humans with an inspiring long-view perspective that encourages constant adaptation in a swiftly changing world, making due with what resources you have, and the symbiotic coexistence with all life on Earth.