Archive for the ‘Natural History’ Category

Monday, April 12th, 2010

‘The Florist’

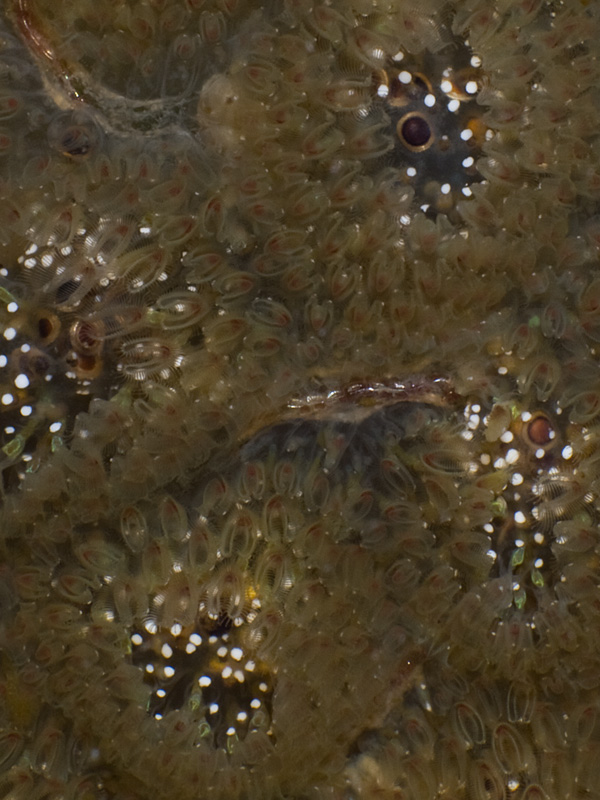

Leptopsia setirostris (Decorator Crab) scavenging amongst a Zoanthus polyp garden

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Once again we return to observe a cryptic red decorator crab (Leptopsia setirostris); this time living upon, and decorated with, zoanthid polyps (Zoanthus sociatus), close cousins to both sea anemones and corals. Zoanthus in Latin literally means ‘animal flower’. The species name sociatus refers to the fact they these flower animals live socially in dense groupings of identical polyps.

Decorator crabs demonstrate a remarkably prescient instinct to be able process the information required to successfully camouflage themselves to match their preferred habitat. Unlike the typically fast-scuttling crabs of the mainstream, decorator crabs move at a deliberately slow pace to reduce being noticed.

This particular decorator crab species boasts a brilliant red exoskeleton that it has disguised with the zoanthids. The crab has carefully nipped individual zoanthid polyps from a larger colony and placed them upon its carapace (back) where they attach down on their own and continue growing. My experience suggests that it takes at least two days for a polyp to begin attaching down to new substrate. I have yet to observe the crab going through the whole process of zoanthid ‘decoration’, but clearly it is a very patient animal.

The crab uses its small claws to pick at and remove pieces of detritus between the polyps. The animal nature of the zoanthids becomes especially apparent when the movements of the crab cause the polyps to close up in reaction. If you look carefully at the bottom right of the screen you’ll notice the periodic movements of a barnacle that these zoanthids are growing upon. Zoanthids are commonly called ‘sea mat’ due to their rubbery, encrusting morphology. They live together in interconnected colonies of cloned polyps, slowly expanding their colonies outward; growing over shells, in-between coral heads, and across shallow tide pools.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Decorator Crab, Morphologic Studios, Natural History, Zoanthid | 1 Comment »

Monday, March 29th, 2010

‘The Lynx Nudibranch’

Phidiana lynceus (Lynx Nudibranch) on Spondylus americanus oyster

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

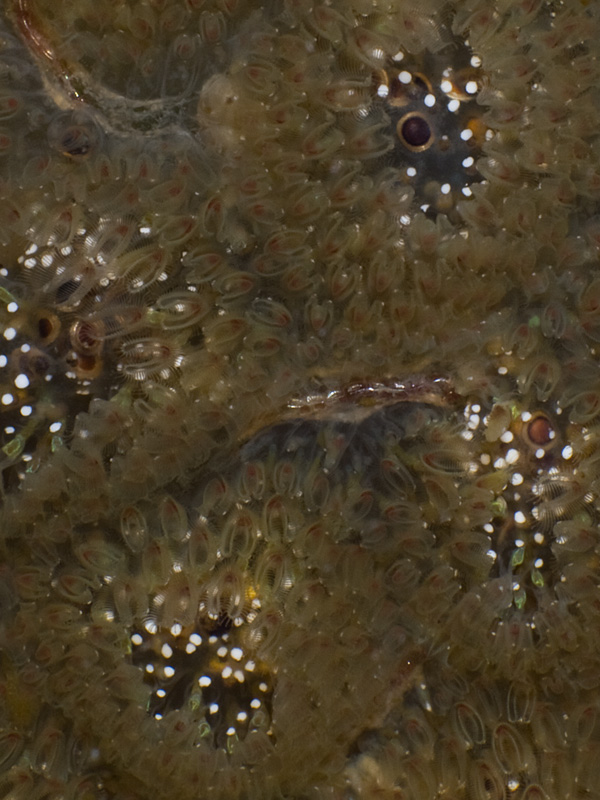

Last week we spent a moment making eyes with the oyster (Spondylus americanus). This week we’ll spend a moment with a diverse community of animals and plants that have colonized the upper shell of the very same oyster. Towards the left of the frame is a small colony of flower-like animals known as hydroids. Hydroids are most closely related to jellyfish, but instead remain attached to the reef their whole lives (unlike a jellyfish). But, like the jellyfish, hydroids can pack a powerful stinging punch. The brown, daisy-like creatures seen growing here on the oysters’s back are one such type of hydroid, Myrionema amboinense. This hydroid species derives its brown coloration from the symbiotic zooxanthellae (dinoflagellate ‘algae’) stored in its tissues. The ability to gain nutrition from both prey capture and photosynthesis, allows these hydroids to grow and colonize quickly. The sting from these hydroids is considerably more powerful than that of most corals. The gray, lumpy knobs on the back of the oyster shell are zoanthid polyps, close cousins of the sea anemones. However, these zoanthids are no match against the powerful sting of the hydroids. The zoanthids have all but acknowledged defeat by the encroaching stingers by simply closing up; effectively handing over control of the oyster shell to the hydroids.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Morphologic Studios, Natural History, The Lynx Nudibranch | 5 Comments »

Monday, March 22nd, 2010

‘Oyster Vision’

Spondylus americanus oyster

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Here we look into the face of the thorny oyster (Spondylus americanus). Unlike most shallow-water oyster species, the thorny oyster is a solitary creature that lives permanently cemented to the deeper coral reef. Its fleshy mantle is adorned with sepia-toned psychedelic camouflage that can vary widely from one individual to the next. The rim of the mantle is lined with dozens of eyes that stare out into the depths. These eyes are quite simple, only detecting changes in light that might suggest an incoming predator. If a threat is detected, the oyster will quickly snap its two shells together, sealing the animal inside with its two powerful adductor muscles. It is the adductor muscle that people eat when they eat ‘oysters on the half shell’. Oysters are filter feeders, spending their time siphoning water through gills that strain out particulate matter. As seen in the film, the oyster periodically expels waste and water with a quick contraction of its adductor muscles.

In the second installment (next week) we will explore the upper shell of the oyster and the community of organisms that has colonized it.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Morphologic Studios, Natural History, Thorny Oyster | 4 Comments »

Monday, March 15th, 2010

‘Transparency’

Unidentified shrimp on unidentified Ricordea polyp

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

In the second installment of the ‘Unidentified Ricordea Shrimp’ series we find the (previously featured) unidentified Ricordea shrimp upon an unusual host. While it is is most certainly on a Ricordea polyp, we are not convinced that it is in fact Ricordea florida. Over the years, we have noticed several key morphological and physiological differences that suggest that there are two genetically distinct morphs of Ricordea florida. For practical purposes, we have been referring to the morph of Ricordea seen here (under 470 nm light) as ‘inshore ricordea’.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Coral Reef, Morphologic Studios, Unidentified Ricordea, Unidentified Shrimp | 1 Comment »

Monday, March 8th, 2010

‘The Arrow Crab’

Stenorhynchus seticornis or ‘Arrow Crab’ guarding a cave entrance

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Take a moment to look into the compound eyes of the arrow crab (Stenorhynchus seticornis). If NASA is looking for a robot capable of navigating rocky planetary terrain, the arrow crab would be a perfect organism to model it after. In the video we look down the sharp, pointed rostrum (‘nose’) of an arrow crab as it appears bobbing in space. In reality, its spindly, spider-like legs are holding it anchored like a sentinel, guarding the opening of a small cave.

Arrow crabs are an abundant species on Floridian reefs, living perched near cracks and crevices in coral heads where they can retreat if threatened. Their pointed rostrum, triangular body, and protruding eyes gives this crab the appearance of a predatory lizard fish that can dash away at a moment’s notice. Instead, the arrow crab is rather slow moving, relying on the fact that the paucity of meat inside the spiny, twig-like exoskeleton of the arrow crab makes it unappetizing to a would-be-predator. This unique anatomical configuration likely explains their abundance in the wild.

Like other decapod crustaceans, the arrow crab has 10 legs (8 walking legs, and 2 pincers or ‘chelipeds’ properly). However, if you look carefully, you’ll notice that this particular crab is missing the last leg on the right side of its body. Fortunately, crustaceans are capable of regrowing amputated legs. Only a few hours after it was filmed, this arrow crab molted, and as if by magic, regenerated its tenth limb.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Aquarium, Arrow Crab, Coral, Coral Morphologic, Morphologic Studios | 1 Comment »

Monday, February 22nd, 2010

‘The Fire Coral’ Pt. 1

A feeding Balanus sp. barnacle encrusted by Millepora alcicornis

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Millepora alcicornis, or fire coral, is not actually a true coral, but a hydrocoral. Hydrocorals are colonies of hydroids that secrete a shared limestone skeleton, making them more closely related to jellyfish than true corals. Here in Florida, fire coral is extremely abundant on our reefs where they serve as the underwater equivalent of a sunburn to unsuspecting divers. Skin contact with fire coral will result in immediate burning pain, followed by an itchy welt that can last for several days.

Fire coral is frequently found encrusting over neighboring corals, starting from the bottom and slowly killing the coral until the colony is completely encased in living limestone. Because fire coral contains symbiotic zooxanthellae (like most tropical stony corals), they are capable of fast growth rates that help build a coral reef. Upon close inspection of fire coral, the stinging polyps can be seen as needle-like projections. At even closer magnification, grape-like bunches of stinging nematocysts can been seen protruding along the polyps’ length. These polyps are retractable, and when an edible food particle is captured, it can be drawn back towards one of the many mouths that dot the surface of the colony. In the video we see a colony of barnacle shells (Balanus sp.) that have been encrusted by fire coral. Unlike the corals though, the barnacle can continue to live beneath the veneer of fire coral.

Barnacles are most commonly found living in the inter-tidal zone where they live periodic lifestyles of low tide rest and high tide activity. When immersed in water, the barnacle feeds with legs specialized for feeding called cirri. The cirri are covered with comb-like filaments that rake the water for passing plankton. If a particle is caught in the cirri, it is drawn back to the animal’s mouth and eaten. When barnacle larvae settle out of the floating plankton themselves, they permanently affix themselves to a life-long location. Barnacles have a special ‘cement gland’ under their bodies that produces an impressive proteinaceous adhesive that holds the animal firmly, in spite of the heaviest of waves. A series of calcareous plates (commonly six) form a turret that protects their soft bodily tissues from predators. Despite their simple appearance, barnacles are in fact crustaceans, like shrimp, crabs, and lobsters.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: barnacle, Coral Morphologic, crustacean, Fire Coral, Millepora alcicornis, Morphologic Studios | No Comments »

Monday, February 15th, 2010

‘The Sun Coral’

The feeding of a Tubastrea coccinea coral cluster

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

This week’s video features a colony of Tubastrea coccinea coral polyp clones feeding on passing zooplankton. The film is sped up 10 times to emphasize the feeding abilities and coordination between the sticky tentacles and the polyps’ mouths.

Tubastrea coccinea or ‘Sun Corals’, have an unusual background story, being the only invasive stony coral to become established in the Caribbean basin. Native to the tropical Indo-Pacific Oceans, they were first noted living on ships’ hulls in Puerto Rico and Curacao (Southern Caribbean) in the mid 1940’s. Over the ensuing decades, they eventually spread elsewhere throughout the entire Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico on the prevailing water currents. It is believed that these sun corals may have originally entered our region as larval stow-aways in the ballast water of intercontinental ships that passed through the Panama Canal.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Morphologic Studios, Tubastrea coccinea | 1 Comment »

Monday, February 8th, 2010

‘Lima scabra’

The tentacles and mantle of a Lima scabra file clam filter feeding

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Lima scabra is a common resident on Floridian and Caribbean reefs where it can be found wedged in crevices, with only its long tentacles extending out into the water column. Usually these tentacles are crimson red (as seen in the specimen above), although they are occasionally white in color. Lima scabra can grow to about 3.5 (9cm) inches long.

Like most bivalves, Lima scabra is a filter feeder. It siphons water in through its fleshy mantle (seen in the video), and strains any edible particulate matter before pumping the water back it out. It holds itself semi-permanently in place through the use of ‘byssus threads’. The threads are formed by a viscous protein secretion that cures instantly upon contact with seawater. These byssus threads have captured the attention of bio-engineers who seek to replicate their strong adhesive properties for industrial applications. However, if the clam comes under attack from a predator, it is capable of detaching and swimming away. They can move surprisingly quick; swimming in fast, jerky movements, propelled by the repeated snapping-together of its shell.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Aquarium, Coral Morphologic, Flame Scallop, Morphologic Studios | No Comments »

Sunday, January 31st, 2010

‘Purple Forest’

Decorator Crab (Microphrys bicornuta) on Asparagopsis taxiformis algae

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

This week’s video features an aquascape comprised of the beautiful purple macro algae Asparagopsis taxiformis. However, if you pay close attention to the left 1/3 of the screen, you’ll notice something… moving with claws. Nestled amongst the algae is a perfectly camouflaged decorator crab (Microphrys bicornuta). Keep paying attention… at 26 seconds into the clip you’ll notice a tiny isopod crustacean float by in the current and descend helicopter-style right onto the crab’s back. The unsuspecting isopod has no idea that it has landed upon an algae covered beast. Furthermore, it appears that the crab is not aware of the unexpected visitor until the isopod begins to explore its decorated exoskeleton. 50 seconds into the clip the isopod meets its fate with a few swift snatches of the crab’s claws. Without missing a beat, the crab continues scavenging amongst the rocks and algae. And life on the reef goes on.

Decorator crabs are amazing creatures in that they pick up pieces of their surrounding habitat and place them on their carapace (back, exoskeleton) in order to blend into their surroundings. Decorator crabs that live amongst sponges decorate with sponges, those that live amongst zoanthids use zoanthids, and so on. This instinctual logic is truly remarkable. The crab in the video has attached small pieces of the Asparagopsis upon itself, and as a result is all but indistinguishable from its surroundings.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Algae, Aquarium, Coral, Coral Morphologic, Decorator Crab, Morphologic Studios, Natural History, Video | No Comments »

Monday, January 25th, 2010

‘Corynactis viridis’

The feeding of a Corynactis viridis corallimorph

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

This past week we finally received our long awaited Corynactis viridis from our good friend Dr. Yvan Perez at the Institut Méditerranéen d’Ecologie in Marseilles, France. I collected these polyps this past June while diving in the Mediterranean, and Dr. Perez has been culturing them in his lab in the interim. Laurent Foure, the current curator of the Noumea Aquarium in New Caledonia, also collected us several stunning morphs from a different Mediterranean location before he left for the South Pacific.

Corynactis viridis is an archetypal corallimorph species found all along the cold, rocky coastlines of Western Europe. Its distribution across the Mediterranean is much more sporadic and considerably less common. They are frequently referred to as ‘jewel anemones’, which is a misnomer, as they are not anemones despite their superficial resemblance. Typically, polyps range in size from about 3-10mm in diameter and can be found in a seemingly limitless number of color morphs. What they lack in individual size, however, they make up for in colonial dominance. It is not uncommon for colonies to completely carpet large areas, frequently rocky outcrops and vertical surfaces. As these colonies are comprised of clones, this carpet will be of uniform coloration, creating the illusion of a singular connected organism. Multiple color morphs will often be found living in close proximity, creating a technicolor patchwork of tiny individuals. Their colors are often vibrant with fluorescent accents. Unlike most of our tropical corallimorphs, C. viridis are non-photosynthetic, relying entirely on the capture of plankton by their sticky tentacles. At the end of each tentacle is a small ball known as an acrosphere; a tell-tale characteristic of all non-photosynthetic corallimorphs.

In this video a single Corynactis viridis polyp (about 8mm in diameter) is seen capturing and digesting tiny plankton as they flow past in the current. As the tentacles capture food, they retract towards the animal’s mouth, located at the center of the polyp. The mouth is likewise transformable; capable of extending, expanding, and enveloping food items. The total elapsed time was roughly 12 minutes and sped up 1200% in order to demonstrate the hydraulic muscular contractions and contortions that the polyp goes through while feeding. 470nm LED light is used to highlight the fluorescent orange ring around the outer diameter of the polyp.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Corynactis viridis, Natural History, Video | 2 Comments »

Monday, January 18th, 2010

‘The Christmas Tree Worm’

Spirobranchus giganteus – Amber Morph

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Christmas tree worms (Spirobranchus giganteus) are an abundant creature on Floridian reefs, making their permanent homes encased inside the limestone skeletons of live coral. Found in a seemingly endless variety of colors and measuring 2-3 cm in diameter, dozens of these worms will typically adorn massive coral heads in local waters.

Using only the perception of light and vibration, these animals will retract at lighting speed at the first sense of something ominous approaching. Fortunately the worms come equipped with a a protective double-horned operculum that seals the worm safely inside the impenetrable coral. A sharp, calcareous spike extends forward of the tube’s opening, acting as a further deterrent to a would-be predator.

The spiraled, ‘branchial crown’ serves as both breathing and feeding apparatus for the worm, and is the only part of the worm’s body that is extended into the water column. The feathery appendages, known radioles, collect plankton that drift by in the current. The radioles are lined with cilia that direct the captured food down the spiral to the worm’s mouth.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Christmas Tree Worm, Coral Morphologic, Natural History, Video | No Comments »

Monday, January 11th, 2010

‘Preener’

Mithraculus cinctimanus crab on Ricordea florida corallimorphs

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2010 Coral Morphologic

Shown above is a 1cm Mithraculus cinctimanus, commonly known as the banded clinging crab. Typically this species is known to live in association with a variety of Caribbean sea anemone species. However, several years ago we noticed that juvenile and sub-adult banded clinging crabs seemed to prefer the protection amongst Ricordea florida polyps in the wild. When they are small, like this one, the carapace (shell) of the crab is nearly entirely covered by a fuzzy red algal camouflage. As they get larger (up to 25mm) they lose much of this hairy coat, revealing a striking white and maroon patterned exoskeleton.

The video shows the crab alternating between preening its own algae covered carapace and the fluorescent tentacles of the Ricordea florida on which it lives. It is possible that the crab may ingest some of the polyps’ mucus as an occasional food source. The video was sped up considerably (9x). At normal speed the polyps appear static, but at this speed the regular hydraulic undulations and contractions of the R. florida polyps are clearly visible.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: banded clinging crab, Coral Morphologic, Corallimorph, Natural History, Ricordea florida, Video | 2 Comments »

Monday, December 28th, 2009

‘Cleaner Pt. 2’

Periclemenes pedersoni shrimp on Ricordea florida corallimorphs

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2009 Coral Morphologic

Here a 2 centimeter Periclemenes pedersoni shrimp is seen perched on its host colony of fluorescent orange Ricordea florida corallimorphs. Pederson’s shrimp are native to Floridian and Caribbean waters, and are found in symbiotic association with a variety of sea anemone and corallimorph species. Pederson’s shrimp live amongst the tentacles of these animals, immune from their sting. They act as ‘cleaners’ of much larger fish. The shrimp wave their antennae and swim in a characteristic swaying motion to signal that they are ‘open for business’. Fish seem to learn and remember the specific location of these ‘cleaning stations’, returning as needed for service. When not removing parasites from fish, these shrimp will forage for bits of food amongst its host’s tentacles and spend time preening itself, as can be observed in the video. Pederson’s shrimp form monogamous mated pairs that will live together on same host. These shrimp are quite territorial, fighting fiercely with its own kind if another Pederson’s shrimp tries to take up residence on its anemone or corallimorph. If an ‘unmated’ shrimp tries to take up residence too close to an established territory, the invader will usually be dissuaded through threat displays and physical harassment.

Pederson’s shrimp are closely related to the spotted cleaner shrimp (Periclimenes yucatanicus) featured last month.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Perderson's shrimp, Ricordea florida, Video | No Comments »

Saturday, November 21st, 2009

‘Cleaner Pt. 1’

Periclimenes yucatanicus shrimp on Condylactis gigantea sea anemone

Music, Video, and Aquarium

2009 Coral Morphologic

Here a three centimeter Periclimenes yucatanicus (spotted cleaner shrimp) preens its exoskeleton and gills amongst the tentacles of a Condylactis gigantea sea anemone. P. yucatanicus is a relatively common species that lives in association with sea anemones and corallimorphs here in Florida and throughout the Caribbean. The stinging tentacles of their hosts provide them with protection from would-be predators. However, despite its vulnerable size, these shrimp act as ‘cleaners’ of larger fish. They remove and consume any parasites and dead tissue they find, often from the fish’s teeth. These fish clearly perceive the benefits of the shrimp’s cleaning abilities over its value as a tiny morsel. This particular Condylactis gigantea has a fluorescent green oral disc which is unusual for the species.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Condylactis gigantea, Coral Morphologic, Periclimenes yucatanicus, Video | No Comments »

Friday, October 9th, 2009

An unusual colony of Discosoma sanctithomae with perfectly spherical vesicles from the Florida Keys at 10m of depth. Note the turbid sea floor, characteristic of this species’ preferred habitat.

The unusual spherical vesicles of these Discosoma sanctithomae polyps once gave this morph a separate species designation Orinia torpida by Duchassaing & Michelotti in 1860. Despite several other taxonomists re-examining the single preserved specimen in the Zoological Museum of Turin in the first half of the 20th century, it was the late great corallimorph taxonomist J. C. Den Hartog who finally corrected this error in 1980. It is understandable that such confusion could occur. Until the advent of scuba diving, many taxonomists would never actually observe the living marine animals they classified. Instead these Euro-centric scientists would rely on preserved specimens sent back to them from various collection missions around the world. With few specimen samples to compare with, morphologic oddities like the pictured polyps could easily be considered to be something entirely new.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, corallimorpharia, Discosoma sanctithomae, Natural History, Orinia torpida | No Comments »

Monday, September 21st, 2009

A close-up of a staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) branch tip. Note the healthy coral polyp extension.

This past Saturday I took my friend Jeremy (of coralpedia.org) and his wife on a shore dive off Fort Lauderdale Beach. I had heard rumors that decent stands of the endangered staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) were abundant in this area. Despite (relatively) poor visibility, we found these rumors to be correct. Acropora cervicornis was one of, if not the most, common stony corals only 250-350 meters offshore this popular sunbathing mecca in only 6-7 meters of water. It is amazing to see how even a small ‘bush’ of A. cervicornis can attract dozens of small fish seeking refuge amongst its branches. It is clear that the widespread die-off of this single species has had a detrimental impact on the entire ecosystem of the Florida’s coral reefs. I can only imagine what the reefs in the Florida Keys were like 30 years ago, as today most are just lumpy humps of rock dominated by massive coral heads, gorgonians, and macroalgae. The interstices of A. cervicornis branches provides a habitat that is unmatched. Seeing an abundance of A. cervicornis so close to shore in Fort Lauderdale is encouraging.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, coralpedia.org, Fort Lauderdale Beach, Natural History, Staghorn Coral | 1 Comment »

Thursday, September 10th, 2009

The spongy decorator crab (Marcocoeloma trispinosum) takes expert care in snipping off pieces of living sponge and attaching them to its carapace (exoskeleton shell). Detritus and debris are added for additional camouflaging effect. This particular crab has taken the decoration to the next level by including some spectacular zoanthids (Zoanthus sp.) into its design. As you can imagine, the crab was living amongst a colony of the same zoanthid morph, rendering it nearly impossible to detect. Furthermore, decorator crabs move very slowly and deliberately, quite unlike the unpredictable scurry of most other crabs. The purposeful addition of camouflaging marine life to the body of this crab highlights the evolution and subconscious intelligence of ‘tool-use’ at such a ‘primitive’ level in the animal kingdom.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Decorator Crab, Natural History | 3 Comments »

Wednesday, August 26th, 2009

A close up of a colony of Pectinatella magnifica zooids; a freshwater bryozoan.

Pectinatella magnifica is another example of a coral reef cousin that I found living in a freshwater lake in Maine, alongside the previously featured Spongilla sp. sponge. From a distance, the colonies that these animals create appear as large jelly-like masses that might be confused with frog’s eggs (see photo below). They are typically found encrusting submerged tree branches, plants, and rocks. Most bryozoans are found in saltwater, but a few species such as P. magnifica are found in freshwater habitats. It would be forgivable to call the individual animals ‘polyps’, as they are superficially coral-like. However, unlike cnidarian (coral-like animals) polyps, bryozoan zooids have a complete digestive system with a separate mouth and anus, whereas cnidarian polyps have a single mouth/ anus opening.

If you look closely at the macro photo you will notice a couple of worms that are living in casings between the valleys that separate sub-colonial groupings of the zooids. The worms were wriggling constantly, most likely in an effort to create a water flow through their tubes that would draw in food items. It would be interesting to know whether these worms are specific only to Pectinatella magnifica, or whether they are simply opportunistic.

The full-sized colony of Pectinatella magnifica looks and feels a lot like a mass of frog’s eggs. It has encrusted over a submerged pine twig.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Bryozoan, Coral Morphologic, Maine, Natural History, New Hampshire | No Comments »

Monday, August 17th, 2009

This freshwater sponge (Spongilla sp.) was found encrusting a submerged tree branch near the shoreline of a small lake in Maine. Note the small oval arthropods living on the surface of the sponge near the middle of the photo.

I recently returned from a short vacation to New Hampshire/ Maine to see family and stomp the formative grounds (and waters) of my youth. While paddling around the small lake that I spent my summers, I found an abundance of this freshwater sponge (Spongilla sp.) growing submerged near the shoreline. Growing on rocks it has a flat, encrusting morphology. On submerged branches it forms lumpy encrustations. And on shallow muddy bottoms it sends up skinny tendrils. The tissue is colored bright green due to a symbiotic association with algae. While you might find yourself thinking “freshwater sponge? really?”, these sponges can be found across most of North America from Alaska south to Florida in relatively still freshwater lakes and ponds. As a testament to their adaptability, this sponge can ‘degenerate’ into a dormant state, forming tiny cysts called gemmules. These gemmules act as ‘seeds’ when favorable conditions return. The sponges reproduce sexually in the summertime and release free swimming larvae. Next time you find yourself at a lake, take a closer look at what you might otherwise think is just some lumpy ‘algae’.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Maine, Natural History, New Hampshire, Spongilla | No Comments »

Wednesday, July 8th, 2009

A toothsome ‘sand diver’ lizardfish Synodus intermedius waits patiently for a smaller fish to come a little bit closer.

On Tuesday morning, our newest team member Graham and I made a shore dive just underneath the flight path of the Fort Lauderdale International Airport (FLL). I’d read that there was some decent shore diving in the area, but I have very little experience in this neck of the woods. 95% of all my dives in Florida have been in the Keys. It was a nice change of pace, although if you go yourself, don’t expect to see the level of diversity and coral coverage you might find further south or offshore.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Natural History, Perciformes, South Florida | No Comments »

Thursday, July 2nd, 2009

Success! The Quest is complete.

For the third dive we had a definitive lead on where we’d find the Corynactis viridis. My friend Laurent Foure is the curator of the public aquarium in Cap d’Agde; about 2.5 hours westward along the coast of the Mediterranean. Laurant is an avid diver, and is very familiar with the marine environment nearby his aquarium. He was able to connect us with a dive operator who could take us by boat to a dive spot inhabited by Corynactis viridis.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, corallimorpharia, Marseille, Mediterranean, Natural History | 2 Comments »

Tuesday, June 23rd, 2009

Not your average Aiptasia. This Aiptasia mutabilis is the largest and most beautiful Aiptasia anemone I’ve ever seen. This one is about 10cm in diameter.

For the second dive on the ‘Corynactis Quest’ we moved 8 km east towards Marseille to a small and picturesque harbor village called Redonne…

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Marseille, Mediterranean, Natural History | No Comments »

Friday, June 19th, 2009

Echinaster sepositus sea star with Parazoanthus axinellae zoanthids.

From June 1-9 I was in France on a a two-fold mission. The first half of the trip was spent in the south of France in Marseille and the surrounding area. I stayed with my good friend Yvan Perez, a professor at the Institute of Mediterranean Ecology and Paleo-Ecology at the University of Provence in Marseille. Yvan acted as my dive guide and translator as we searched along the coast for the temperate Eastern Atlantic/Mediterranean corallimorph Corynactis viridis.

The second half of the trip was spent in Strasbourg in the Alsace region of France near the German border where I gave a lecture on the Caribbean corallimorph species at the annual convention of Recif France, which is the society of French reef aquarists. Over the next couple of weeks I will be posting a series of articles on this trip, specifically the quest for Corynactis viridis…

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Marseille, Mediterranean, Natural History, Recif France, Two Little Fishies | 1 Comment »

Wednesday, January 14th, 2009

If you ever find yourself having to cross the southern portion of Florida, you’ll have the privelege of transecting the Florida Everglades. For most people, this involves taking I-75, aka “Alligator Alley”, which is four lanes wide and moves quickly when there isn’t a major hold-up (which is somehow more often that you’d like). Given that the flow of traffic usually moves in excess of 80 mph, it is quite unlikely that you will get to see any of its namesake reptiles.

A much more scenic route, that will actually reward you with an alligator or four, is to take the Tamiami Trail, aka Highway 41. The road is only two lanes, but still manages to cruise at a comfortable 60 mph with relatively few hold ups or traffic. The Tamiami Trail crosses Florida to the south of I-75, and takes you through a picturesque cross-section of the Everglades. Along the way you’ll find rest stops, nature trails, and Miccosukee-owned road side attractions that give this route great Floridian character.

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Big Cypress, Coral Morphologic, Everglades, Natural History, South Florida | No Comments »

Wednesday, October 22nd, 2008

I spent this past Sunday morning slogging through the eastern edge of the Miccosukee Everglades. The Everglades, at the tail end of a bountiful rainy season, are finally looking like the river of grass that they ought to be. For the past several years South Florida has been in a serious drought, but this year has brought us a much needed replenishment of rainwater.

More photos below the jump…

(more…)

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Everglades, Miccosukee, Natural History, South Florida | No Comments »

Saturday, July 19th, 2008

Last week I had the opportunity to shoot some photos of the Maine seashore while on vacation. The Gulf of Maine is known for many things, mainly lobsters, but some less glamorous life-forms are attracting some renewed attention for good reason in this time of finite resources.

Rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum), a type of fucoid seaweed adorns the barnacled, wave-worn Appalachian rocks along some 3,000 miles of New England seashore. Rockweed serves as a habitat for small invertebrates and fish, which in turn provide nourishment to the many seabirds that make the Gulf of Maine a perfect migratory outpost. Essentially, Rockweed enables an entire food-chain of organisms normally incapable of surviving extreme weather, temperature, and voracious predators to thrive and in turn create a most healthy shoreline.

European colonists quickly found Rockweed to be an excellent agricultural fertilizer, and began harvesting the seemingly endless supply of this “weed.” These days, Rockweed is processed to extract carageenan-like compounds called “alginates” that are used as stabilizer/thickener agents in some our most common day-to-day products like cosmetics, toothpastes, and soups. While commercial benefits of this seaweed are vast, a sustainable harvest is of high priority, considering over-harvesting this macro algae can have negative effects on ecosystems both above and below the water.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Fucales, Gulf of Maine, Natural History | No Comments »

Wednesday, May 21st, 2008

Red Mangrove with nearly mature propagules in front of Duck Key, FL.

It’s that time of the year again in the Florida Keys. Summer is all but here and the red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) are almost ready to drop their mature propagules (a seed pod if you will). These propagules are quite unique in that they become fully formed “plants” even before they fall off the tree (They have already germinated while on the tree itself). When mature, they drop into the water below and float iceberg-style, carried to new locales by water currents, wind, tides, and storms. In ideal circumstances the propagule eventually finds a soft bottom in which to take root. The leaves form from the top of the propagule. Eventually it will produce the iconic mangrove prop root “legs” that help facilitate gas exchange and structural support.

This form of reproduction makes propagating mangroves in saltwater aquaria a relatively easy task. All they need to grow is for the top 1/3 of the propagule to be above the water surface, bright light, a deep sand bed, and occasional “mistings” of freshwater from a spray bottle to wash off built-up salt deposits. These are trees of course, so expect them to eventually grow quite large.

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Coral Morphologic, Florida Keys, Malpighiales, Natural History | No Comments »

Saturday, May 10th, 2008

In the second installment of the mandarinfish saga, I describe a unique method of catching the blue mandarin dragonet (Synchiropus splendidus) that doesn’t involve using cyanide or nets. It involves using a teeny-tiny spear gun to (more-or-less) harmlessly capture this beautiful fish. It may sound barbaric, but I conclude that it is relatively harmless, and a less harmful alternative to sodium cyanide poisoning.

Click here to read more about this novel ornamental fishing technique…

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Bali, Coral Morphologic, Natural History, Perciformes | No Comments »

Saturday, May 3rd, 2008

From August 2006 until April 2007 I lived in Bali, Indonesia working as an intern with the Marine Aquarium Council (MAC Indo). My primary job was writing a simple coral mariculture manual (lagoon-based) useful for local fishermen as a “how to guide”. However, I was also able to follow along on MAC’s primary duties in the field, working with the local ornamental fisherman groups throughout Indonesia.

I have finally had some free time to sift through my journals and photographs, and look forward to posting some interesting articles on the marine aquarium trade in the future.

In this first installment, I describe the natural history of the blue mandarinfish (Synchiropus splendidus) a popular reef aquarium fish. In the second installment I will go on to describe a fishing technique that doesn’t involve using cyanide or nets. It involves using a teeny-tiny spear gun to (more-or-less) harmlessly capture this beautiful fish. It may sound barbaric, but I conclude that it is relatively harmless, and a superior alternative to sodium cyanide poisoning.

Click here to read more about the natural history and courtship behaviors of the blue mandarinfish…

Posted in Natural History | Tags: Bali, Coral Morphologic, Natural History, Perciformes | No Comments »