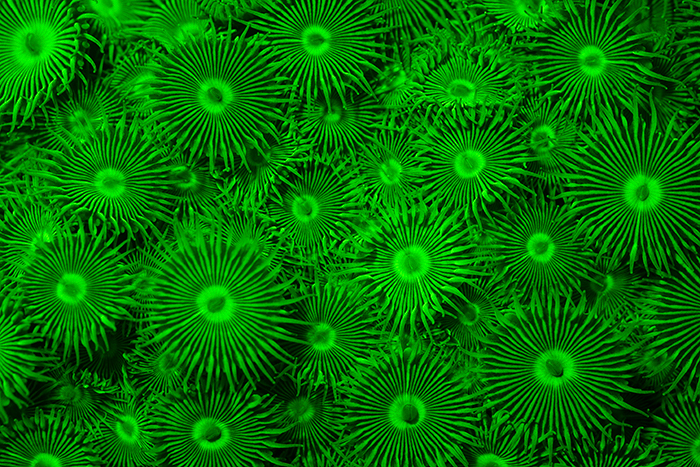

New Species of Soft Coral Discovered on PortMiami’s Seawall Contains a Powerful Anti-Cancer Drug

These Palythoa sp. zoantharians contain a remarkably potent chemical, palytoxin, proven to selectively destroy cancerous cells.

Several years ago we were excited to report that our survey of Zoantharian soft corals from South Florida had resulted in the identification of several undescribed species. Today, we are even more excited to report that one of these Palythoa species zoantharians, collected off the PortMiami seawall, contains an extremely powerful compound with proven anti-cancer properties. Coral Biome, our partners in Europe, have officially received a patent for the chemical’s extraction and application in the treatment of cancer and other serious diseases. From Coral Biome’s inception in 2011 in Marseilles, France, we have been assisting them in the collection, identification, and aquaculture of soft corals that produce medically-valuable chemicals, a process known as ‘bioprospecting’.

The chemical Coral Biome isolated, palytoxin, has long been known to be one of the most deadly non-protein compounds in the natural world, however it is only recently that its remarkable anti-cancer properties have come to light. As it turns out, the Palythoa aff. ‘clavata’ we found encrusting Miami’s aquatic infrastructure produces significantly higher concentrations of palytoxin than any species previously known to science. Palytoxin is such an extremely complex molecule to produce in a lab that it has been referred to as ‘the Mt. Everest of organic synthesis’ by chemists. Therefore, production of this chemical for pharmaceutical use will depend on Coral Biome’s patented extraction method from these aquacultured, super-potent Miami zoantharians. Palytoxin kills cells by disrupting the potassium/sodium ion channels, but according to Coral Biome’s CEO Frederic Gault, “it is a million times more toxic to cancer cells than to healthy ones, which is a huge area for potential”. This discovery highlights just how important coral reef biodiversity is to humans, and our pursuit for new medicines and biotechnology. This new species, along with our previously reported hybrid ‘super coral’, highlight once again just how much there is still left to discover right in our own backyard. If a potential breakthrough cure for cancer can be found right here within PortMiami, how many more unidentified species and cures are left to be discovered elsewhere amongst the planet’s thousands of far flung reefs?

The coral reef is an exceptionally good place to prospect for medicinally active compounds, particularly within the soft corals and sponges. While stony corals are largely protected from predators by their limestone skeletons, soft corals and sponges frequently rely on chemicals for their defense mechanisms. In addition to making them distasteful, soft corals will also release growth-inhibiting chemicals into the surrounding water to prevent other organisms from encroaching onto their real estate. And because water is such an ideal medium in which to transfer chemical signals, the coral reef will likely exceed the rainforests as a potential source for future medicinal discoveries. Thankfully, a revolution in coral aquaculture means that we can now obtain these medicinal compounds sustainably, without negatively impacting the wild reefs.

Identifying and using medicinal compounds from the coral reef is not a new phenomenon. From the 1950’s until the 1970’s, the Caribbean gorgonian soft coral Plexaura homomalla was the primary source for extracting the chemical prostaglandin, which is used to induce childbirth clinically. Pseudopterosin A, extracted from the Bahamian gorgonian Antillogorgia elisabethae is used by Estee Lauder to make an exceptionally expensive anti-aging skin cream. But it’s not just the organic chemicals that interest biomedical researchers; stony corals are now being grown in labs to serve as human bone graft substitutes, while the stinging nematocyst cells of corals are serving as a model for developing needle-less vaccine delivery systems. The insertion of coral fluorescent proteins into the genome of other organisms has revolutionized the field of genetics, earning its developers a Nobel Prize in 2008. The recent understanding by scientists of how a coral’s microbiome serves its host has resulted in a paradigm shift in the way we now perceive microbes, human health, and even evolution. The coral reef may well be the most important living model we have for the betterment of human health, making their preservation, with all their untold biological secrets, of paramount importance to us all. And while the reefs around the world head into a third consecutive year for bleaching, never has it been more urgent to catalog and clone the global biodiversity of coral for the collective benefit of us all.