Miami Coral Rescue Retrospective & Urban Coral Hypothesis

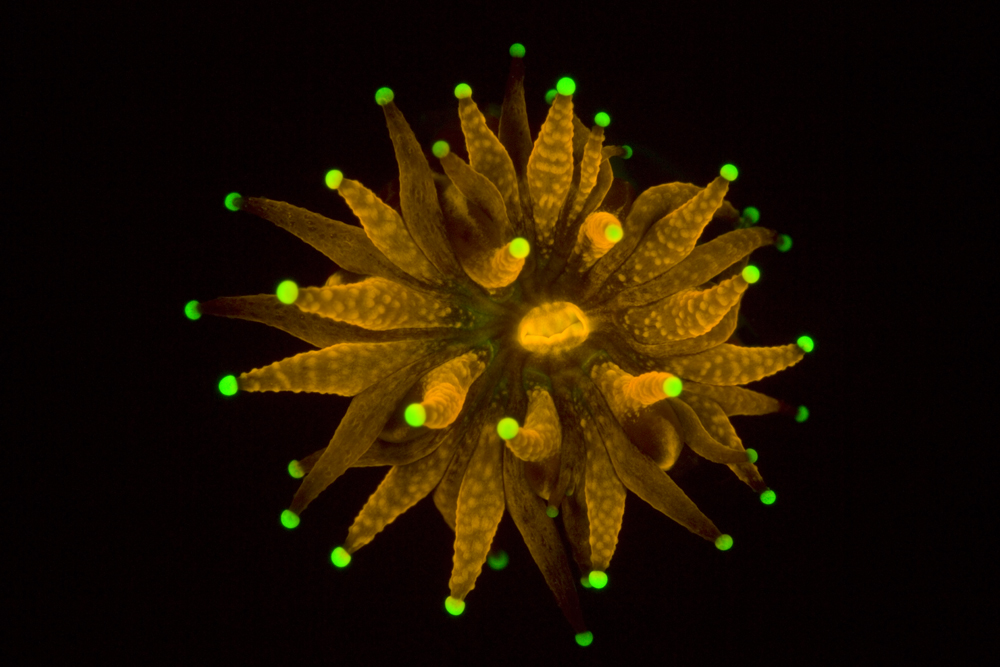

A hyper-fluorescent juvenile Montastrea cavernosa rescued from Government Cut.

After months of impatiently watching dredge ships working offshore Miami, Coral Morphologic and other researchers were finally granted a brief window of opportunity from May 26 until June 6th in which to rescue corals left behind from the legally-required relocation effort from the Army Corps of Engineers’ Deep Dredge of Government Cut. This was a much shorter length of time than we had been prepared for, and as such, we had to respond with considerable urgency in order to rescue as many corals as possible. Fortunately we had begun our detailed preparations in January 2014 by coordinating students and professors from the University of Miami to help in the effort. Collectively, the Miami Coral Rescue Mission removed over 2,000 stony corals that would have otherwise been destroyed in the process to make way for the larger ships that will pass through the soon-to-be-expanded Panama Canal.

The majority of the corals that Coral Morphologic removed from Government Cut have now been transplanted to an artificial reef about one mile south from where they originated, and where we will continue to monitor them to ensure their long-term survival. Some corals will be sent to the Smithsonian Institution for research. And the rest of the corals were brought back to our Lab, where we will document them via film and photography for a body of work titled ‘Coral City’, in which we will present them as fluorescent icons for a 21st century Miami.

While we could have rescued more corals with an extended deadline, the Miami Coral Rescue Mission is not over. It is now entering a longer-term monitoring phase in which we will continue to assess the health of surrounding coral reefs through July 2015, when the Deep Dredge project is finally slated for completion.

Read a New York Times article on the rescue mission and listen to an NPR story below covering a day out on the water. Click the link below the NPR story to read the remainder of this post.

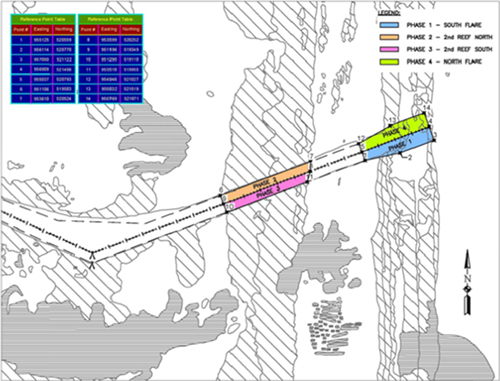

With two separate natural reef systems bisecting Government Cut, and each with their own north and south sides, we only had a few days to try and clear each of the four distinct areas. We concentrated our efforts on the outermost reef, where the Army Corps will be dynamiting to expand the entryway into the shipping channel. As seen in the video below, this hybrid manmade/ natural aquascape is packed with a multitude of tropical fish that call Government Cut home. Sadly, this underwater habitat will be destroyed by dynamite in October 2014. But fortunately, the vast majority of corals have now been removed from this area on the third reef tract.

A serene scene as hundreds of tropical fish swimming along the manmade aquascape of the south side of the third reef tract. This area is slated for destruction by dynamite in October 2014.

While the dynamiting may seem to be the most destructive threat, our primary long-term concern is now shifted towards monitoring the levels of silt produced by the Deep Dredge, which will continue non-stop for the next year. Based on our current observations of nearby corals on the natural reef, we are uncertain whether they can survive being smothered by constant silt deposition from the dredge operation.

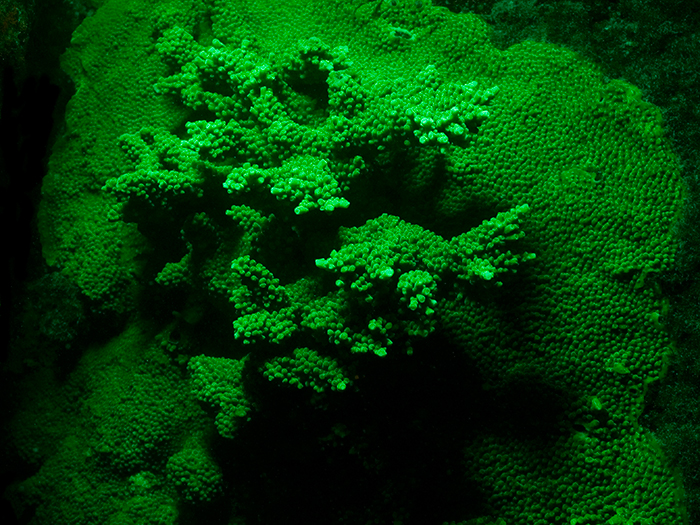

Our concerns for over-sedimentation are supported by our in-situ observations of corals living on top of the second reef which are barely visible under a blanket of silt. On the second reef, our window for diving was limited to a 2 hour period at high tide, at which point we were still limited to about 15’ visibility. Corals are already showing bleaching stress along the base of their colonies due to ever-deepening silt deposits on the seafloor. Furthermore, in the April 2014 Interagency progress report on the Deep Dredge, it was acknowledged that sedimentation blocks used to measure the amount of silt falling to the seafloor are not working properly. When asked by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection if the Corps intended to replace them with working sediment traps, they responded that they would not. If the equipment necessary for determining the sedimentation rates is not accurate or functional, who will be held accountable if in fact the corals on nearby reefs are smothered or stressed?

Coral Morphologic’s interest in Miami’s ‘urban corals’ began in earnest in 2009 when we first discovered a rare hybrid staghorn/ elkhorn coral living along the shoreline of Fisher Island in Government Cut. If such an unusual coral could live so close to the city, it made us wonder what other corals we’d find living deeper into Miami. Further exploration revealed an extraordinary biological diversity of coral reef organisms that have taken advantage of Miami’s man-made marine habitats; ranging from concrete seawalls, trashed shopping carts, to the shipping channels themselves. By 2011 we had formed the basis of our ‘urban coral hypothesis’, which posits that corals taking advantage of Miami’s manmade infrastructure may in fact be more resilient and adaptable than their natural reef counterparts (and therefore incredibly important to research).

This hybrid staghorn/ elkhorn coral is a prime example of the unusual corals worth researching inside Miami’s urban waterways.

It is astounding that such delicate organisms are capable of surviving amongst the high levels of bacteria and chemicals that are regularly observed in North Biscayne Bay. Because corals are animals without a built-in immune system, they instead rely on a multitude of microorganisms (microflora) that live in balance to keep the coral healthy. Collectively, the coral animal and all of its symbionts are known as the holobiont. It appears that many of the diseases impacting Florida’s wild reefs are being caused by infections that disrupt the balance of the corals’ holobiotic community. In fact, the transmission of pathogenic bacteria from human gut flora has been confirmed to cause the elkhorn coral disease white pox, a particularly deadly infection for these grand old reef builders of Florida past. Elkhorn coral is but one of dozens of other species of stony corals that have self-populated Miami’s urban coral laboratory. In fact, we’ve identified 4 undescribed species of soft corals living on artificial substrate in Miami, one of which we are investigating for its biochemical potential.

We see Miami as an inadvertent and unique coral laboratory. And we hypothesize that its corals may hold the secrets to understanding how corals worldwide will be able to adapt to changing climate and water chemistry in the decades to come. This is a laboratory that could only be created via a century of complete ecosystem re-engineering to accommodate the cosmopolites. It is in fact a collateral benefit to the billions of dollars taxpayers have spent on developing a major cosmopolitan city adjacent to a natural coral reef. The corals growing in these newly formed environments are ideal research subjects for coral biologists who are trying to understand the adaptive stress responses of corals. As such, we view Government Cut as being the most critical component to Miami’s urban coral ecosystem. This shipping channel creates a tidal sluiceway that starts 3 miles offshore (beyond the third reef tract) and ends in Downtown Miami at Museum Park (the terminus of the original Port of Miami). Each high tide funnels clean water into the city from far offshore… including larval recruits that may have been carried internationally by the Gulf stream current. Likewise, at every low tide, Government Cut allows the nutrient rich water from the city to flush back out to sea. This alternating flushing action from Government Cut helps to keep North Biscayne clean, and allows corals to pioneer deeper into the city.

While we are sad to see the dredge destroy any corals or reef habitat, and we are not happy about the next 13 months of high sedimentation on Miami’s marine environment, we ultimately see the deepening of Government Cut as just another piece of the experiment that is Miami. By deepening it an additional 8’ (from 48’ to 54’), it will likely increase the volume of water exchange that happens with every changing tide. In the long term, we hypothesize that the health and water quality of Biscayne Bay will be improved, and expect to find more corals pioneering ever deeper into the City. It will be scientifically valuable for us to document the re-colonization of the freshly dredged channel over the coming decade. A new experiment begins.

This Army Corps of Engineers map highlights the second and third reef tracts where we were permitted to collect these so-called ‘corals of opportunity’ in Government Cut.

Miami is a paradise built on porous limestone in a drained swampland, where the Everglades meets the reef, at the nexus of extreme hurricane probability, and just a few miles from the most powerful oceanic current on Earth. It is a crucible for understanding how coastal cities and their marine environments will manage to adapt to global climate change.

When the highest natural elevation in the city is a fossilized coral reef (Cutler Ridge), it puts things into perspective… it was once completely underwater. Likewise, the third reef tract far offshore is a reminder of a time when the water level was much lower. The geological point here is that Miami has always been in a state of fluctuation; a battle between fresh and saltwater. The sands of the beach are always shifting. The city of Miami that we live in today is nothing like the ecosystem the Tequesta Indians would have experienced just a few hundred years ago. For instance, there were certainly no corals living at the mouth of the Miami River like there are today. In the past hundred years the terrestrial ecosystem has become overrun with a botanical garden’s worth of nonnative tropical plants and a zoo’s worth of invasive animals. There is no ‘going back’. Instead, Miami must look ahead and prepare to become resilient. These pioneering corals demonstrate life’s tenacious ability to adapt in unbelievable ways. Miami’s urban aquatic ecosystem gives us hope that corals worldwide will be able to adapt and survive, just as they have for the past half billion years. If anything, it is us, the citizens of planet Earth, that must learn to accept that constant change is the new reality, tomorrow is uncertain, and that we must be prepared to adapt always. With corals already growing along Biscayne Boulevard, it is clear to us that it is the coral that will inherit Miami if mankind ever gives up. And if they don’t, they will still colonize the pilings that support buildings erected out of the very limestone concrete that contains the ground skeletons of their ancestors.

Team Coral.